Substack's free speech moderation question

We're trying to do digital-age politics with categories and ideas from the analog world. I may as well throw out my modest proposal for an online republicanism built around the public sphere.

Substack’s catching the ire of the hall monitors and it’s on us to keep it open.

I’ve spilled a good portion of words here talking about abstract issues of artificial intelligence. It may not seem like it yet, but many afflictions of culture and political life today, those most visible in the Extremely Online world of social media, are symptoms of the mechanization of life that creates so many puzzles around AI.

Everything is mechanical now. All problems are engineering. Salvation will come from a 23 year old in a hoodie making the next killer app, dude. Give your favorite tech-overlord what he wants and you’ll live forever in virtual reality paradise.

Then we have Substack’s new Notes feature. It took all of a week of public access before The Grievances started. The struggle sessions come down to a single question.

Just how much of that freedom of expression are you willing to tolerate, son?

Somebody has to do something. Action, however mindless and counter-productive, must be taken to make sure that unspecified awful things don’t happen.

I’m going to wander a bit, but the thesis is straightforward. We can’t talk reasonably about moderation and censorship and free speech and all of that because modern ethical and political thought is not equipped for it.

In this piece I’m going to say some opinionated things about freedom, rights, and where I think Substack should go.

I don’t make it a habit of wading into political discussions.

I find that a pointless waste of time when done on the internet, without a pint or three of beer splitting the table between us. But then I went and done it.

My position here cuts between both the radical absolutism endorsed by anime avatar accounts and the perceived need for finer tastes and discrimination in our moderation, what as to keep the discourses civil and uptight against the rabble.

The other reason I don’t comment on politics is down to my idiosyncratic views about human life, which start in my ideas on ethics and politics.

If you’re familiar with the lingo, I’m what you could call a neo-Aristotelian, but not a religious sort in the way most understand that term, which makes an odd combination.

Let me summarize what means in a few bullet points:

I believe there is such a thing as human flourishing. There are some ways that a human life can go well, and many more ways which it goes badly.

Not all goals are good, right, and praise-worthy just because someone wants them or chooses them. People can be mistaken about what is good in a life as well as how to get it.

The qualities and virtues of a person’s character are no less important than their deeds. Character is action, action is character.

Politics is the continuation of ethics, aimed at the excellence and flourishing of the citizens of the community. Political life promotes and encourages specific ideals of the good life.

The good life involves participation in the life and self-rule of one’s community. This fact demands certain civic virtues associated with citizenship. Belonging to a community is about more than personal “what’s in it for me?” self-interest.

These political goods are as important and valuable as the goods of autonomy and independence. A well-run society will, likewise, take autonomy and self-determination seriously among its common goods.

These positions put me at odds with the great majority of modern ethical and political thinking, across the spectrum from ancap libertarians to Marxist vanguards.

Endorsing a positive conception of human goodness is a big no-no today.

We don’t say that this way of living is better than that way. To do so runs up against all our intuitions about egalitarianism and tolerance and such things. You’re not supposed to judge someone else. Can you imagine a worse crime?

We don’t talk about the good. Instead, we set up neutral procedures of law and economics that handle our disagreements. Instead of having a grand 30 year war to decide whether Protestantism is the superior faith to Catholicism, we can leave the moral questions to private conscience and keep public life regulated by the blind scales of Lady Justice. Let the market handle it, or the lawyers.

But comes a question: What about peoples, nations, and cultures that don’t agree with our minimal standards of what is acceptable to a reasonable person?

What if your culture and traditions and institutions don’t recognize any difference between public and private spheres?

As it happens, this is the reality for many people alive right now, as it was through most of history.

The hands-off tolerance of political liberalism officially endorses no moral ideals of how one ought to live. In practice, procedural tolerance of difference amounts to a vision of the good life as robust as any classical religion. Human lives tend to go well when we agree to disagree and get on with the business of living.

This, reader, leads us into two pitfalls with potentially ruinous consequences:

It’s difficult to recognize any goods beyond autonomy and non-interference.

When faced with agitators pushing for other goods, like “minimizing harm”, we’re forced back into liberalism’s distinctions of form/substance and public/private, unable to engage with the question of what is worthy.

Let’s have a look at these.

What other goods are there beyond autonomy?

Way back in the Politics, Aristotle extended his discussion of ethics — which addressed right conduct aimed at the good life — to the concerns of public life in the community. Once we’ve worked through what is right and proper and good for a single person, the next step is to figure out how that works out when we live with each other.

And we do have to live with each other. If the human being is the animal with logos, with reason and speech, we are also the zoion politikon, the political animal. We are essentially social creatures who live in relationships of mutual need and dependence. From family roles to friendships and much more beyond, there is no individual without a shared life with others.

That social character of human persons, along with their moral aspects, are casualties of modern political thought. Today, each of us is thought of first as a pre-political atom of selfhood, a private center of rationality or subjective feeling that is a world unto itself. Societies large and small are nothing more than aggregates of these atomic selves.

The self is primary and essential. The community is derivative and accidental.

Rousseau and those influenced by him went as far as to consider social life and language as optional extras tacked on to human nature, mere tools demanded by the contingencies of society, as if we could conceive of a healthy human being living without speech or even family ties. This is as nonsensical as speaking of four sided triangles and married bachelors, but the romantic individual remains an influential ideal even today.

In today’s discussions of the good and the right, the autonomy and independence of the atomic self takes center stage. Other goods either derive from liberty or contribute to it as means to that end.

Aristotle and later writers under his influence recognized the importance of liberty, although they saw liberty as a political matter.

One is free who is not a slave. The idea that a person’s liberty depends on certain inviolable rights, guaranteeing a minimal space for expression and ownership and so forth, didn’t appear until many centuries later.

The development of rights in European thought is, to my mind, a genuine innovation in political thinking. I’m not one of these traditionalists who outright rejects anything with the stench of modern ideas. But I do believe that liberalism, untempered by older ways of thinking, loses something in the wash.

One thing we have lost is recognizing liberty as not only situated in a community — one is free with others — but as one good among many goods in a life. Yes, liberty is a worthy goal in itself, and I’d never think to argue otherwise, but so are many other worthy and excellent ends.

Social and political life today comes down to “what’s in it for me?”

Common life in the community is a function of satisfying interests and desires. “But what about the less fortunate?” you ask. “Surely they receive care from us, and ought to. And surely they aren’t looking out for themselves.”

Are you so sure of that? The poor and the meek are after the same self-interested goals as the rest of us. Their stake in political life is the same as everyone else: to get their share of the pie. The great arguments in political life today come down, for the most part, to questions of how the goods of society and economy ought to be distributed among the rabble. If you buy the liberal humanist story, we’re all looking to climb the hierarchy. All that we’ve called goodness and value (etc.) is really power and self-interest.

Ideals of responsibility to the community, and I mean to the community as a whole, to that enduring horizon of history and meaning which is beyond any one of us, are either non-existent — see the extreme ancap libertarians — or reduced to the edicts of condescending bureaucrats and experts who know what’s best for you, no matter what you think about it. Paraphrasing Rousseau, you’ll be made to be free, and like it.

Genuine community spirit and its virtues are, if not yet dead, in the terminal stages of life support.

How do we handle the illiberal streak built into liberalism?

How to engage with anti-liberals while affirming liberal goods

If “liberty” is a bad master ideal, emotive slogans like “avoiding harm” and “do good” are no better. There’s a discussion to have here about the meaning of moral words and value judgments, which we aren’t going to have. For now let it suffice to say that these expressions are so vague and abstract that they have no meaning. There is no really-existing thing to which they refer. Philosophers call these “thin concepts”. They’re lacking in the concrete substance needed for meaningful language.

I don’t know what “harm” means except relative to particular cases of actual injury.

If a mugger holds me at gunpoint, takes my wallet, and pistol whips me, that’s a pretty clear case of harm. It’s much less clear to me that “harm” as an umbrella term, generalizing from particular cases of injury or wrongdoing, has any meaning. Certainly not the way the word is used as a bludgeon by activists who want to associate mugging with mean and nasty internet words.

The word does have a powerful use in appealing to moral emotions, including the propagandist’s favorite go-to motivators of fear, guilt, and shame.

The use of blunt moral concepts like “harm” and “good” is an old piece of unconvincing moral philosophy borrowed from classical utilitarianism. “Do good” and “minimize harm” are defined as some measurable quantity. More happiness, less suffering, more people with satisfied preferences, what have you.

This appeals to the intuitions of systemizing and analytical personalities, the types who are likely to be academics and researchers and write on these topics as public intellectuals.

This preference has much more to do with the fact that brute quantities are easier to measure and calculate with, and less because they are appropriate or accurate expressions of moral judgments and beliefs. The algorithm really does take everything.

That strategy depends on their being any such thing as “good” to predicate of a description — pleasure is good, suffering is bad — and that’s not an easy view to defend. Check the link for if you want to know more on this:

What’s missing here?

The obvious thing, and the problem I’ll get most flak for, is all the material conditions, economics, biology, social factors, and plain old power that are beyond the scope of this discussion. I’m interested in the philosophical ideas, so that’s what I’m looking at.

At that level, liberalism doesn’t have any handy ways of addressing the problem of “good” since it’s designed to avoid talking about goodness and virtue and other “thick” concepts. Good is a personal matter, not for politics or philosophers. Seen that way, you can see liberalism as a collaborator — or infection vector — for non-egalitarian and illiberal politics of all sorts.

The difficulties with thin concepts of good come into relief if we look to Aristotle’s thinking on ethics and politics.

Aristotle is known best for his ethics of virtue. The virtues involve more specific, concrete forms of evaluation than we find in thin concepts of “good” or “harm”. His work concerns not “good” flat and simple — that concept had no meaning for him as it did for Plato — but precise kinds of excellence for specific kinds of thing, according to their nature.1

Courage is an excellence of character that lies between the two defects of cowardice and stupid aggression. To judge an action or a person as courageous is to say that they have acted rightly on an occasion.

Here’s a pitfall: This is not to claim that courage “is good” without qualification. Courage is good for a human being, in respect of how human lives go well in particular respects of desire and behavior.

This is a subtle but crucial detail. We can be good or bad, right or wrong, in many different ways. There isn’t a single one-size-fits-all concept of good that you either are or aren’t in the way an apple is red or not. There is no way to call a state like pleasure “good” in absolute terms.

The diversity of goods brings all of us into unavoidable conflicts.

Take the virtues of justice and charity. A virtuous person is a just person, and a charitable person. But the demands of justice are often in conflict with the demands of charity. Fairness can be harsh, kindness often unjust.

What does the virtuous person do? There is no single universal standard or decision procedure to make the call. A good deal of practical thinking comes down to the exercise of wisdom in a situation, responding appropriately to the circumstances and these competing demands of the virtues. The idea of a universal decision procedure that applies always and everywhere is a non-starter.

The point is this:

There is always a conception of the good life, a purpose to human living which is our aim and end, at work in our actions and judgments. But that good life is often mutable and situational, and it is partly dependent on our nature as beings who are capable, in part, of self-determination.

Freedom is part of virtue, and freedom responds to virtue.

These complex facts about ethics are deeply relevant to how we live together.

Readers of Aristotle, ancient and modern, have found in his work a basis for a political theory that we know today as republicanism. This has nothing to do with capital-R Republicans in American politics. Republicanism is a form of political life organized around self-rule, participation, and civic virtues. The people, res publica, are involved together in joint self-determination. In exercising self-rule they demonstrate virtues that are amenable to self-determination and the life of the community.

The ethical demands of self-determination and the politics of self-rule come as a package. Participation demands responsibility, and vice versa. Done right, you get the modern innovations of personal autonomy with the traditional practices and institutions of shared communal life with kin and kith.

Point is, the citizen has a personal stake in the community and its flourishing, and the community itself, ruled by its citizens, takes the flourishing of its members as its aim.

You don’t get that when a clique of screaming activists imposes their will on the majority through coercion, manipulation, and moral blackmail. You don’t get that when a clique of self-appointed experts imposes a vision of “correct thinking and desiring” on the rabble from above. You don’t get that when it’s every atomized person out for his or her own self-interest, either.

Each of these represent contrasting ideals on a spectrum. The deontic wish-fulfillment language, full of “they should”, “we need to”, “when will they”, “if only they would”, is fantasy. It doesn’t matter if you’re wishing for everyone to be a self-responsible entrepreneur, a bleeding-heart out to end all possibility of suffering, or an over-educated manager who believes you know better than the unwashed rubes.

Isaiah Berlin warned of the threat of positive liberty throughout his writing.

Positive liberty is the type of freedom that results from an achievement, typically a form of self-mastery. You don’t have liberty, as with the natural rights tradition; you earn it.

Trouble is, as Rousseau wrote — inspiring generations of thinkers in this mold — an act doesn’t count as coercion if its for your own good. Whether you know that or not is irrelevant. What is for your own good is what you would want if you knew better, so we’ll give it to you good and hard.

Berlin was rightly suspicious of all claims of positive liberty, associating such ideals with the worst forms of totalitarian ambition — all in the name of freedom, equality, and human betterment, you understand.

This won’t do, no more than ideals of absolute (or negative) freedom of the person can result in a viable polity. Allowing others to decide what is in your best interests for you, without asking or caring about your own views, in the name of “democracy” or “doing good”, is the height of smug intellectual hubris. The catastrophic consequences of these beliefs, which left behind pyramids of skulls and mass graves within living memory, ought not be forgotten so easily.

Yet here we are.

Let’s take stock. Absolute individualism severs the person from community, nature, and more. Collective welfarism destroys the individual in the name of ideals (or ideology).

What do we do?

There are levels in between absolute individualism and absolute collectivism. But we can’t talk about those while locked into the false binary of modern thought, where they are the only options.

What do we do?

The remedy is not more procedures, or more fidelity to norms and standards of rights, or (may God help us all) better models or scientific theories of behavior held out by The Experts. Some of these are important, perhaps even vital, and I don’t dispute that. But they need to be supported by our own image of a robust and vital good life. And they need to be restrained from the excesses that tend to destroy their targets.

Rule-loving midwits, from parliamentarians to hall monitors on social media, love making rules, and they hate doing the hard work of being involved and setting the standards.

Here’s the thing. I don’t agree with absolutism about free speech. Every community has norms and conventions, even if they’re tacit and unspoken. The defenders of “tolerance” and “diversity” have their own sacred taboos hidden away under the epicycles of logical incoherence that make up their (alleged) ideas.

You’re free to say anything (but not that). — This is expected and healthy. The question is not about whether speech will have limits.

The question is what shall be verboten, for what reasons, and how that will be decided.

That’s the real discussion we aren’t having, at any scale. For my part, I will not be blackmailed into a cure worse than the disease.

Alexis de Tocqueville once warned that democratic life based in radical individualism would inevitably collapse into a tyranny where majority opinion and goals become homogeneous, disintegrating the bonds of local community and leaving the individual to fend for himself against nature and State.

The atomization of social life paves the way the centralized State to take command, filling the void once occupied by vibrant local communities. Today, we have no real intermediaries between the individual and unchecked State power.

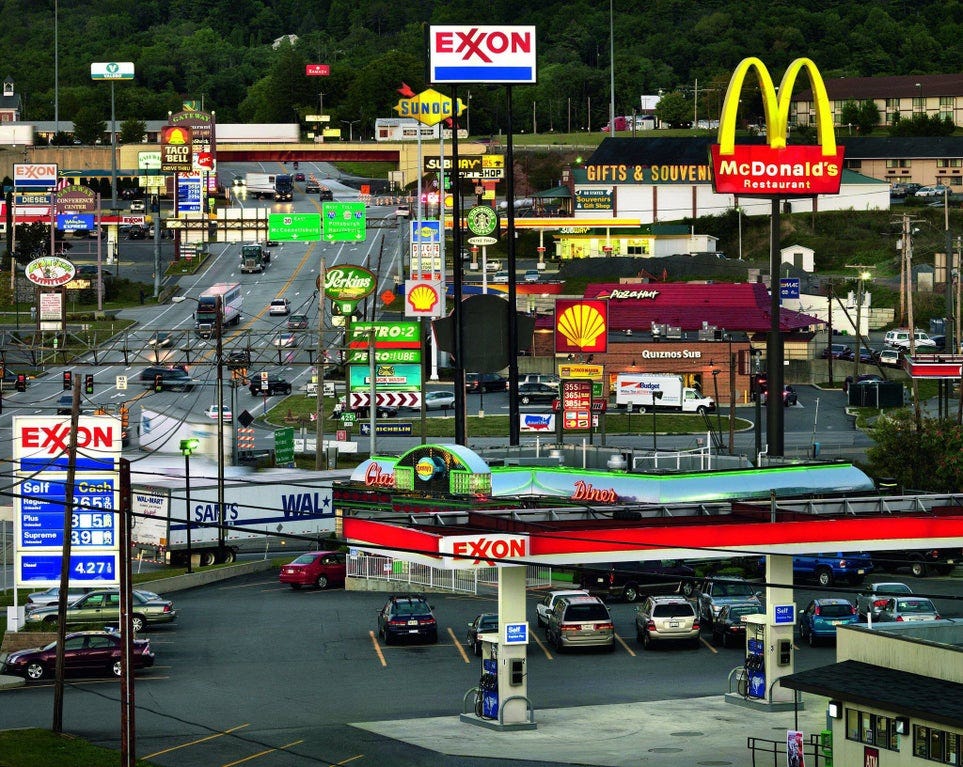

Tocqueville really nailed that one. In the US, what was once a diverse and varied patchwork of localities and communities had melted into an indistinguishable chimera of chain restaurants, shops, and supermarkets connected by interstate highways, airports, and internet.

Once everything and everyone becomes equal, there is no more difference to speak of. Absolute individualism concludes in absolute sameness.

That is my fear and concern over this call for centralized moderation and top-down control.

The same solutions, endorsed by the same people, to enforce the same habits of thought and desire, and all under the ironic rubrics of “equality” and “democracy” and “diversity”.

Bottom Line:

We on the pro-speech side are encouraging healthy debate and interaction. Where that isn't possible, we encourage curation and filtering. Don’t like it? Don’t look at it.

The other side will not stop until they've rewritten the terms of service and installed their own Ministry of Truth and Safety to monitor and regulate what is said and who can say it.

We're encouraging self-rule and participation, against those agitating for centralized control under a panopticon.

That’s my position, anyway. I make no claims about the motivations or ideas of others, even on “my side”.

The real meat of the dispute isn't about the fact that we disagree, in some ways large and small, over the good life, over the virtues, over fair procedures or equality. The point here is not to come to agreement, to end disagreement, to bring everyone under a happy umbrella of shared goals.

No. The point is to allow space where disagreements can happen.

And that is a question of who shall rule, and in the name of what.

The pro-speech side isn’t really about speech or expression in a vacuum.

The core issues revolve about who gets to participate in rule-making and how the rules will be made.

The republicanism I’ve sketched here, brief and tenuous as it is, strikes me as a model worth imitating, possibly the best bet for navigating between top-down control by the same thought-terminating ideologies everywhere else and rabid chaos.

I’m happy for Substack to take a stand on norms of acceptable speech.

That is unavoidable anyway, and I’d rather it be made explicit instead of hiding it behind opaque Trust & Safety Councils, staffed by anonymous NGOs, and operated with unresponsive layers of automated emails.

Ideally that stand will come with a commitment to the community and its flourishing, with norms of self-rule and participation and actual tolerance of difference, and not the sham “diversity” that hall monitors use as blackmail for totalitarian thought-control.

Ideally the norms here will remain broadly as they are, accepting of most every non-criminal form of expression, encouraging discussion when possible, curation when not.

I even welcome the the blackmailing hall monitors demanding the end of existing norms. They’re welcome to contribute in their ways, and I’m welcome to ignore them and block them at my leisure. As it should be.

Thanks for reading.

-Matt

ps Hit the buttons and share or comment or both.

As the story goes, Aristotle brought Plato’s Form of the Good out of the starry heavens and into the particular things which manifest it. There is a “good” behind all things which are good, but, as far as Aristotle is concerned, goodness depends the function of a thing relative to its kind. A good knife, a good dog, a good farmer, a good city, a good man, and a good source of energy are all good, but good in particular ways. Though a strong case can be made that Plato didn’t believe in a single Good either — but that’s for another time.

You and I are fairly aligned on this issue. Moderation is required for meaningful discussion, but can only be done on the community and individual level, and larger platforms like social media should be more concerned with providing the tools for individual and community moderation than being in the business of moderation themselves. Meanwhile governments should be in the business of ensuring markets are not monopolized or controlled by trusts so that other channels of communication are available to the public, rather than trying to regulate what communication the channels are allowed to air.

Yeah Ive already engaged the enemy today. https://substack.com/profile/14886164-sean-adams/note/c-15156542