John Carpenter suspends natural law until the end of October

How Carpenter's horror movies reveal the sublime wonders and terrors slithering through the entrails of notional reality

When I was fourteen, John Carpenter's The Thing scared me into three weeks of terrified insomnia.

The movie was a staple on the USA Network back in the early 90s. One bored Friday night I settled in to watch what I thought a harmless sci-fi flick. It had Kurt Russell and Wilford Brimley, so how bad could it be?

I made it to the kennel scene. I wasn't ever the same after that.

Horror movies always had a strange fascination for me. I tried to watch Aliens when I was 10 years old, which bothered me so much that I felt anxious at the sight of Sigourney Weaver for years. By the time I was 16 I could watch the original and far scarier Alien without a blink. The series (okay, the first two) became one of my favorites to this day.

I figure that horror is like black coffee. Nobody likes the first taste, but if you give it a few tries, you end up preferring it to the liquid diabetes served up at your favorite coffee chain.

John Carpenter's films do horror with the finesse of a Viennese conductor. They may look like cheesy B-movies, but there's a depth of ideas that elevates his work above the shameless slasher flick.

MP favorite

reminded me of this the other day with a note about Carpenter's best-known film Halloween.Carpenter lays out what made Halloween so effective compared to its lackluster sequels:

Michael Myers was an absence of character. And yet all the sequels are trying to explain that. That’s silliness—it just misses the whole point of the first movie, to me. He’s part person, part supernatural force. The sequels rooted around in motivation. I thought that was a mistake.

Writer Michael Kraus adds:

For only 1978’s Halloween, the first, the best, has the awful and powerful wisdom to know that sometimes, there is no why. No reason, no order. Sometimes, bad things just happen.

Only true nerds will know this, but The Thing is one part of a loosely-connected Apocalypse Trilogy. The other two films, Prince of Darkness (1987) and In the Mouth of Madness (1994), are far lesser known but, in my laudable opinion, no less worthy.

They Live (1988), with its on-the-nose social commentary and Rowdy Roddy Piper, could be taken as an honorary "bonus" installment.

Carpenter's movies each explore this single insight from different angles.

Sometimes, there is no why.

What makes that frightening? Why is it terrifying to experience the absence of reasons?

Most of the waking day happens to us on an unconscious level. You aren't thinking about what you do or why. On occasion your awareness pops up as you attend to a problem, but for the most part we're creatures of habit.

Habits work in environments with a reliable pattern of causes and effects. If there were no stable order, you could never settle into habitual behaviors. The environment would demand your constant attention and you'd be in a state of permanent stress.

When the strange intrudes into the familiar, the accepted order you rely on no longer holds.

Something uncanny ruffles the fabric of existence. That’s horror.

Stephen King tells that horror comes in three levels. The first is the gross-out based in visceral revulsion and disgust. This is the 80s slasher flick, working its power through shock and gratuitous special effects that provoke a gut-level response.

The second level is horror. (Yes, he calls "horror" a type of horror. Go with it.) Horror is the graphic portrayal of the unbelievable. When faced with the implausible and unnatural, the mind struggles to comprehend what cannot be. We respond to the unsettling strangeness with fear.

The third and highest level is terror. Terror is the most powerful and compelling because it creates fear in the imagination. Skilled users of terror don't show you the lurking evil. They suggest it with small details, something ordinary that's off. The audience collaborates with the creator to fill in the blanks with the awful details.

The Thing works on all three levels. The monster itself has become a cult legend thanks to Rob Bottin's stupendous gross-out effects which, unlike the forgettable CGI of the 2011 prequel, hold up after 40 years.

But there's so much more going on. When the monster "eats" a character, it imitates them perfectly, down to memories and behaviors. We're left with the spine-deadening question of whether the victims even know they're victims.

You can't trust the person in front of you to because he might not be himself.

He might not know he's not himself.

You might not be yourself.

The entity by its very nature challenges every belief about solidity, form, and personal identity. The creature -- does that word even apply to it? -- pushes our words and categories to the breaking point and beyond.

We don't know what it is because its nature, which is no more than behavior, challenges our beliefs about "it-ness".

Peel back the flesh you take for granted and find alien awfulness underneath. This monster brings our characters to the black horizon at the end of "why?"

There is no explanation, no reason. Only threat.

Prince of Darkness explores that dizzying territory through the lens of religion and the cutting edges of quantum physics.

If you thought the Thing creature was awful, consider quantum theory. Our best-tested and most accurate scientific knowledge shows that every idea we have about substance, causality, and time is no part of reality at the smallest levels.

There’s only a bizarre, complicated mathematical machinery that makes accurate predictions to many decimal places, while telling us nothing about how the world is. Reasons why have no place here, not even with the world’s creator.

In the Mouth of Madness brings the trilogy to its logical conclusion. The first two movies used biology and physics to undermine our confidence in the stable order of reality. But if that's the case, what's left of science?

Science today is all but impossible without artificial models created in computers. The reality outside of the models is unknown and unknowable. We're now building models of the mind, called Artificial Intelligence, while cognitive science uses those models to study human minds. It’s models all the way down.

When you can no longer tell the difference between the object and the model you use to know the object, where’s the reality in that feedback loop?

You’ve possibly heard of that “Culture War” myth that postmodern relativism challenges science. The truth is much scarier. Extreme relativism is a consequence of science.

If we only know reality through arbitrary signs and symbols called language, then on what grounds do we say that you and I and the world are anything more than a figment of our own imaginations?

What's the difference between a real world and the imagined reality brought into being by writers and artists?

Does it all collapse into a hallucinatory fever-dream?

If The Thing ripped away the flesh to show you a monster, and Prince of Darkness shines a light on the fangs behind Nature and God, In the Mouth of Madness slowly erodes confidence in your own psychological existence.

There is no why.

Carpenter's filmed oeuvre echoes thoughts and themes first explored a century ago in H. P. Lovecraft's weird tales.

Lovecraft's constitutional phobia of the alien made him the first to explore the horrific implications of science. His cosmic horror moves the genre beyond the supernatural ghost story, drawing out the terrifying implications of man's existential situation in a cosmos of staggering dimensions. We're alone in an empty, uncaring universe populated by vast and unimaginably old minds which know us, if they know us at all, the way we know ants in the kitchen (or bacteria in our guts).

Our feeble senses and limited brains give us but the barest glimpse of this universe. We didn’t evolve to entertain such notions. What is a trillion? How far away is a light-year? You can write the digits, but can you entertain the magnitude? What does a four-dimensional cube look like?

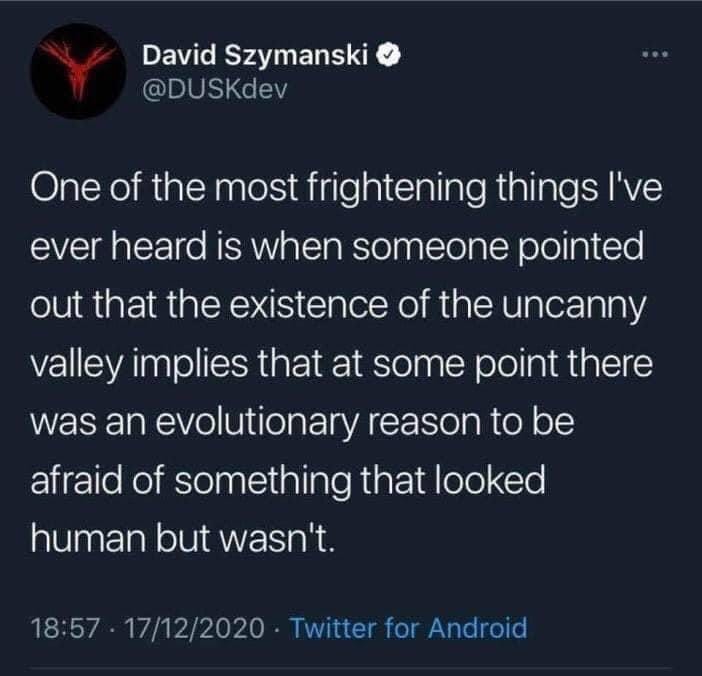

And what do you make of this:

The universe revealed by modern science is horrifying by its mere existence. The mostly-stable order that our bodies and minds must take for granted is not stable at all. Not only is the ordinary world about as secure as liquid gelatin, the facade hides the real causes from us, making useful cover for predators.

Venture too far beyond the familiar fires of home and you risk madness and much worse.

From a creative standpoint, this is why it doesn't pay to explain the monster in a horror story. Today’s storytellers love to explain why the monster exists and why it does what it does, while modern audiences seem unable to enjoy a story that doesn't connect every last dot from start to finish. The fact that so many prequels and reboots and remakes and sequels exist is to make sure everything has a place and all the threads knot together.

The explanation destroys the magic.1

The menacing gods and malevolent demons of mythology, for all their evil, at least belonged to an intelligible order. They had a place in creation. We could comprehend them and give some meaning to their existence.

Carpenter's brand of cosmic horror, like Lovecraft's, forces us to confront lurking terrors waiting out there, in the howling noumena beyond all sense.

Sometimes, there is no "why".

Thanks for reading.

-Matt

p.s. If you found this valuable, interesting, funny, or it made you upset that you had to use your mind for something besides infinite scrolling, I ask that you do me a favor and share it with just one person.

Here's a handy button for you ⤵

If you're new here, go ahead and subscribe. Do it.

While I'm not as down on Ridley Scott's Prometheus as many, I do think the need to explain is the major flaw of the film. I didn't need to know that the grotesque organism-machine in Giger’s derelict spaceship from Alien was actually an 8 foot tall albino bodybuilder. The pilot’s incomprehensible mystery helped create the atmosphere of menace. Not knowing, and never being able to find out, has far more impact than superficial dot-connecting.

Excellent, enjoyable article. A great distillation for fiction writers.

I admit, I can never quite grasp the thing it is that would lead to an aha moment- I assume no one can. I am woefully uneducated in the sciences as well, yet I like reading Meaninful Particulars because you provide so many bits that add to what is my conscious experience. Two things on this one. There is an interesting discussion of what a four dimentional cube might look like in the novel Solenoid and you wrote "The explanation destroys the magic". This is dead on for both horror and life in general.